Updated on 26 May 2020 with contributions from our Chief Scientist Claire Shortt

In our last post we gave a sneak peek at key features of the AIRE digestive tracker, as well as introducing FODMAPs (Fermentable Oligo-saccharides, Di-saccharides, Mono-saccharides And Polyols). In order to get the most out of your AIRE, we’d like to let you know a little bit more about FODMAPs and how hydrogen breath testing can be used to test your ability to absorb them.

What are FODMAPs?

FODMAP is an acronym that stands for:

Fermentable — This means the substance is fermented — broken down — by bacteria in the large intestine.

Oligosaccharides — “Oligo” means “few” and “saccharide” means sugar. Oligosaccharides are made up of individual sugars joined together in a chain. They are found in foods like garlic, onion, baked beans and asparagus.

Disaccharides — “Di” means two. This is a double sugar molecule like lactose, which is found in dairy products.

Monosaccharides — “Mono” means single. This is a single-sugar molecule like fructose, which can be found in many fruits.

And

Polyols — These are sugar alcohols (but not the alcohol that gets you drunk!). These include sorbitol, which occurs in dried fruits like prunes and stone fruits, like peaches. It’s also used as a natural sweetener in things like sugar-free gum and diet drinks.

FODMAPs include carbohydrates like lactose, fructose, sorbitol and inulin, which are found in lots of everyday foods.

How do FODMAPs affect digestion?

More than a decade ago, a team of scientists at Monash University in Australia made one of the biggest international discoveries relating to Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). This discovery has since become the leading recommended diet for people with IBS around the world. The scientists found that, for some people, FODMAPs in everyday foods aren’t fully digested. If this happens, bacteria feed on the FODMAPs once they reach the large intestines. This process is called “fermentation”.

This build-up of gases, such as hydrogen, can lead to symptoms like abdominal pain, bloating and flatulence. We measure hydrogen because people don’t produce it for any other reason, so it serves as a useful marker of when food hasn’t been fully digested.

The scientists at Monash discovered that by eating a diet low in FODMAPs, patients saw significant improvement in their symptoms. An enormous number of people have been able to use this information about the low FODMAP diet to improve their symptoms.

However, the low FODMAP diet can be quite restrictive and isn’t designed for long term use. Since each of the FODMAPs can have different effects on the body, it is important for people to try to identify which specific FODMAPs are a problem for them. For example, you may be able to handle fructose, but not lactose, or vice versa.

Where does breath testing fit in?

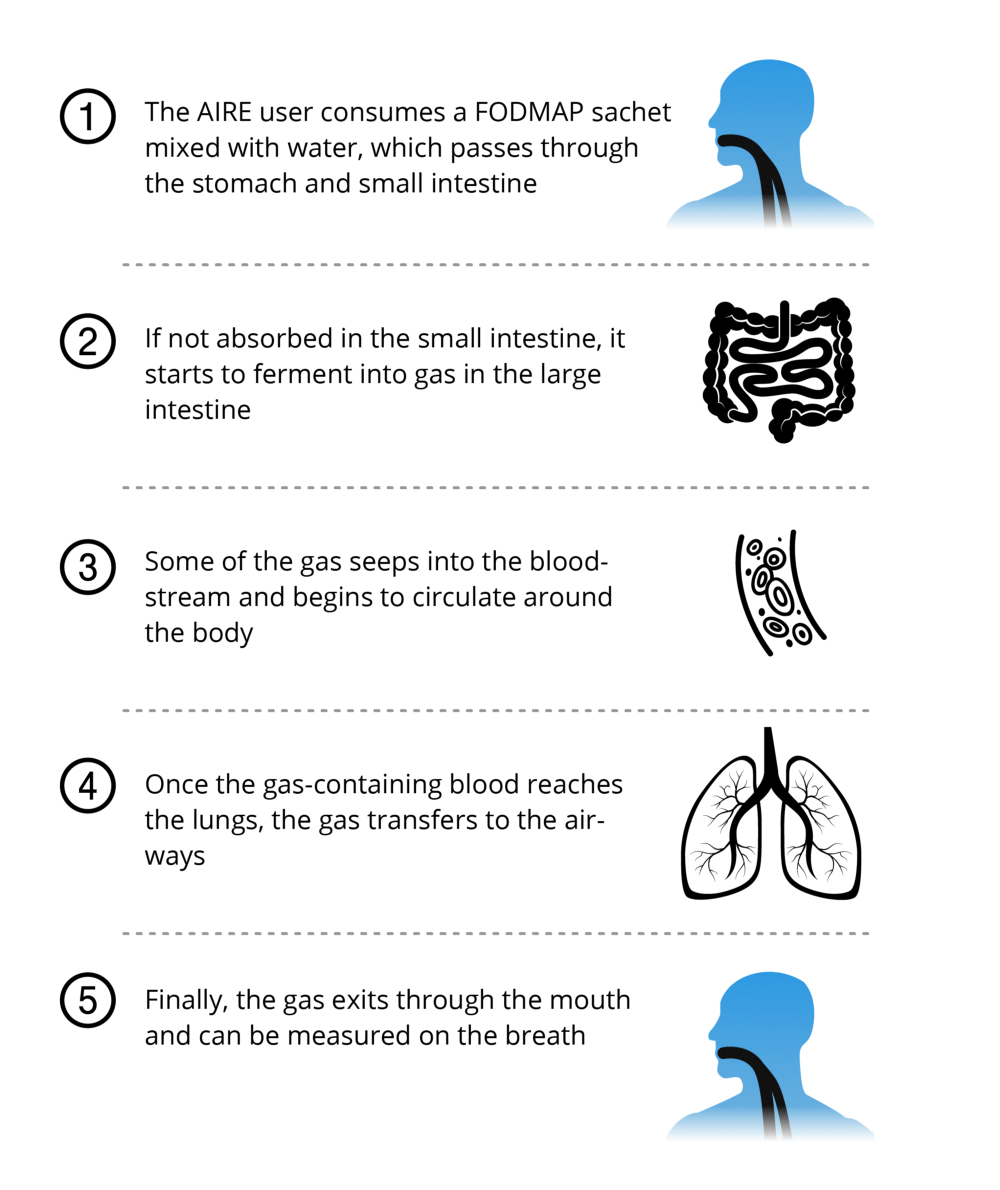

Once a FODMAP reaches the large intestine and is fermented by bacteria, some hydrogen is absorbed into the bloodstream. From there, the blood flows around the body and hydrogen passes into the lungs and is released on the breath.

When doctors want to find out whether their patient is having trouble absorbing a particular FODMAP, they will sometimes order a hydrogen breath test in the hospital. This looks for hydrogen on the breath while the patient digests the FODMAP.

To prepare for these tests, the patient will fast for at least 12 hours. They will then visit the hospital or clinic and breathe into a collection bag. The concentration of hydrogen is measured from the sample to provide a baseline level of hydrogen. Since people don’t naturally produce hydrogen, a person who has been fasting should have very little on their breath.

Once the patient’s base hydrogen level is determined, they drink a glass of water combined with a single FODMAP (e.g. lactose). Breath samples are then collected every 15 minutes, typically for up to three hours.

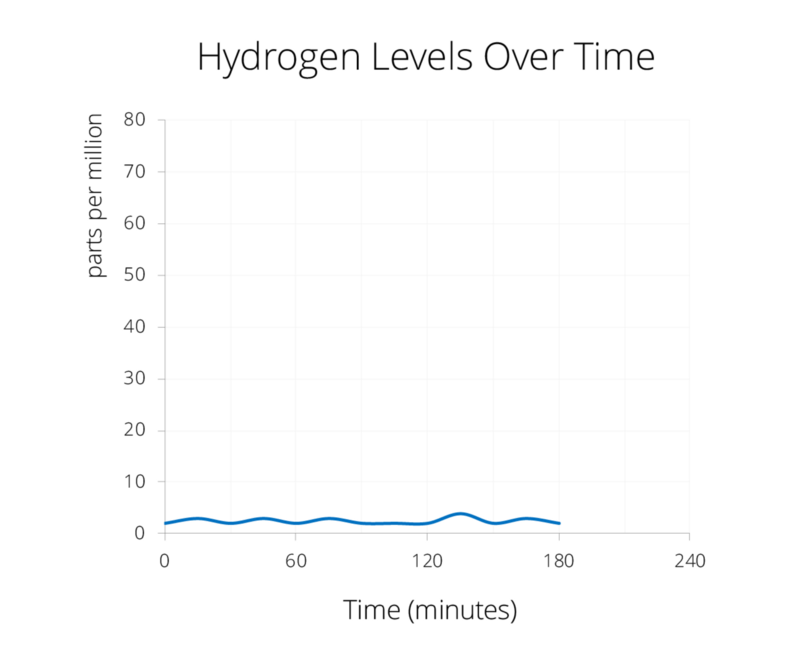

The doctor uses these test results to see how well the FODMAP was absorbed. For example, if a person digests lactose well, their hydrogen levels will remain low throughout the lactose breath test, as shown below.

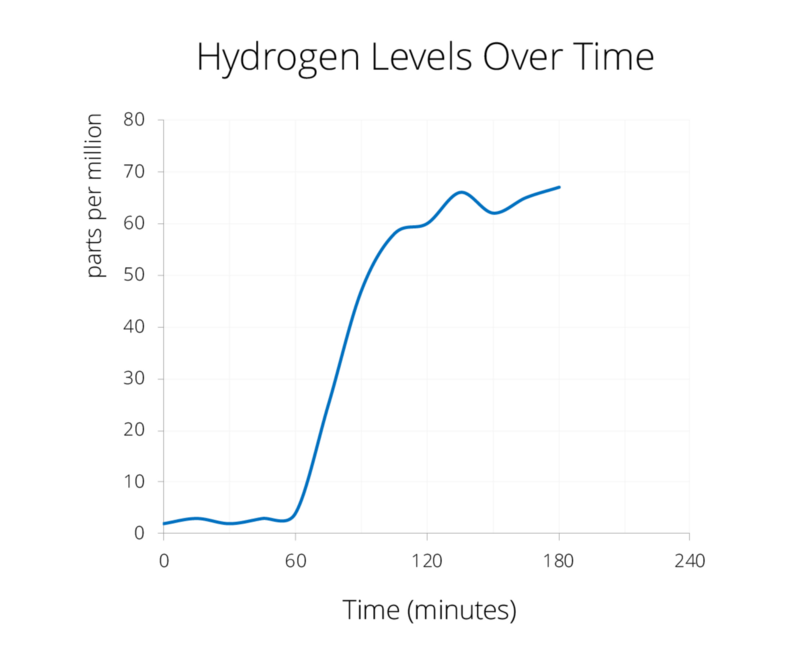

But a person with issues absorbing lactose will see a spike in their hydrogen levels. This indicates that the lactose was not digested fully and so, it reached the large intestine and is being fermented by the gut bacteria.

Since everyone’s digestive system is unique, the amount of time it takes for hydrogen levels to start rising can vary. Most people start to see results in about 60–90 minutes, and levels can drop off quickly after the initial rise or remain high for hours afterwards.

AIRE and hydrogen breath testing

FoodMarble’s AIRE is a digestive tracker that allows you to take hydrogen breath tests at home. AIRE is not a medical device like the ones in hospitals, but uses very similar technology. We wanted to develop a personal, portable device that you can use to check the hydrogen levels in your breath. It comes with an iPhone and Android app so you can view your results instantly, and also lets you track other things that can affect your digestive symptoms, like stress and sleep.

Of course, you should always consult a doctor first if you have severe digestive issues or concerns about your digestive health. We’re excited to give people the opportunity to track their breath hydrogen levels as a step towards better understanding their digestion. You can learn more about how the AIRE Food Challenge feature works here.

-With contributions from Dr. James Brief, FoodMarble co-founder and CMO and Dr. Claire Shortt, FoodMarble Chief Scientist

Watch our video for a quick guide to Hydrogen Breath Testing

FoodMarble AIRE users can also opt to purchase our FODMAP sachets. These can be used to carry out FODMAP Challenges at home.